VICE: The Legal System Failed Two Sex Workers – So They Took Their Rapist to Court

A new play called “No Bad Women” tells the true story of a landmark trial that opened up a new avenue to justice for survivors.

In the 1990s, serial rapist Christopher Davies assaulted two separate women at knifepoint when they visited his house in the south of England. The first – a tattooed biker, mum and former teacher – was told by police that she had no chance of getting justice in court. The second – a woman working in porn to support her disabled husband – was attacked a year later. Both were sex workers, and their case was rejected by the Crown Prosecution Service for insufficient evidence. So they did something extraordinary – the two women took Davies to court themselves.

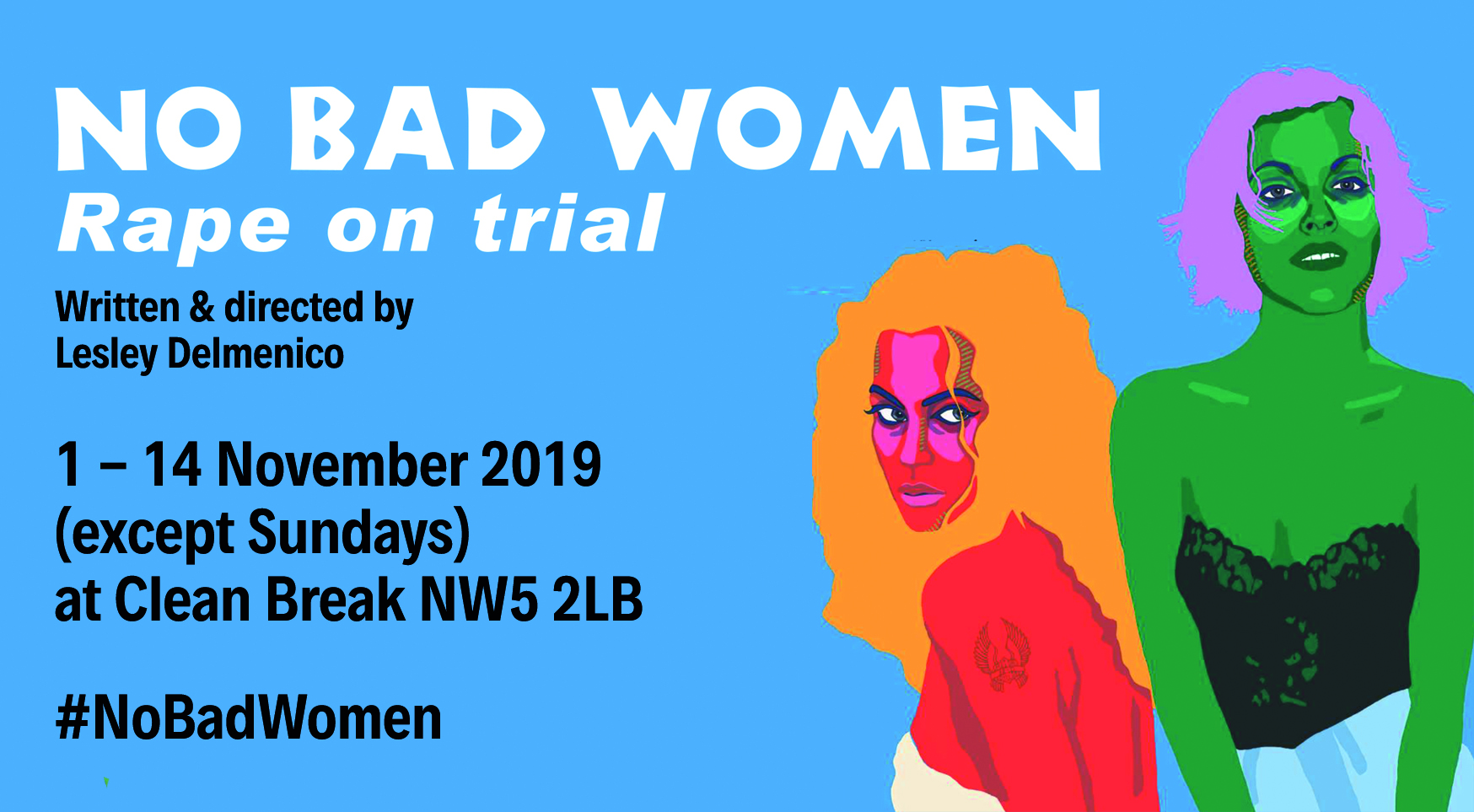

It ended up becoming the first private prosecution for rape in England and Wales – a groundbreaking legal precedent that opened up a new avenue to justice for survivors. It also forms the subject of No Bad Women, a new play based almost verbatim on the resulting court transcript, due to run for two weeks from the 1st of November at Clean Break in Kentish Town.

The CPS’ treatment of the women wasn’t unusual – the vast majority of rape cases in England and Wales don’t lead to a charge or summons. After Davies threatened the first woman’s family when the charges against him were dropped, she approached the English Collective of Prostitutes (ECP) for help getting an injunction. The organisation felt the story was so outrageous that they looked into what else could be done. The ECP often worked with the grassroots organisation Women Against Rape, who offer support, legal advocacy and information to women and girls who have been raped or sexually assaulted. The two groups used their collective power to assemble a legal team to work pro-bono and prosecute the case. It took three and a half years, but eventually went to court in 1995, with both the women and their husbands giving evidence.

The trial itself highlighted a pattern of prejudice within a legal system that prevents women, particularly marginalised women, from seeking justice. Women Against Rape spokeswoman Lisa Longstaff, who helped bring the case to court, says that the group at the time published a dossier of 15 cases that should have been prosecuted by the CPS – cases that bore striking similarities to Davies’ survivors.

“None of them were sex workers, but they were all women who didn’t have a high social status or were related to the attacker,” she explains. “Women who were under 16, women who were married to or partnered with their attacker, women of colour and women with insecure immigration status. You could just see there was prejudice against them, and the woman weren’t backed against the man who, in most cases, had a higher social status.”

Longstaff believes the same is true of the case depicted in No Bad Women. Both women were dismissed simply because they were sex workers. Niki Adams, an ECP spokesperson who also helped bring the case to court, believes that the play addresses the difficulties that sex workers in particular face while trying to navigate the legal system. When sex workers do come forward to report violence, it’s at the risk of being prosecuted themselves on prostitution-related offences such as loitering, soliciting or brothel keeping.

“Sex workers are usually only ever portrayed as poor victims, in order to justify the move to increase criminalisation in the name of saving us from ourselves and from violence, and this is a direct counter to that,” she says. “This is not two victims, this is two women who were victimised and who took their rapist to court – but it’s not a ‘happy hooker’ story either. It’s a real reflection of the reality of who goes into sex work, why, what happens to us, and how we struggle against those injustices.”

The case proved a significant point – not only that sex workers could take their rapist to court, but that a private prosecution could be held on exactly the same evidence provided to the CPS when they rejected it. Of course, during the trial the women still faced the same prejudices the CPS had in the beginning, with the defence barrister focussing on the fact that they were sex workers, attempting to discredit their character, and accusing them of lying for criminal injuries compensation. Shockingly, it was only after the trial that it emerged that Davies had served a 12-month jail term in 1988 for attempting to kidnap a 20-year-old woman at knifepoint.

It was Women Against Rape who suggested, many years later, to turn the trial into a play when Lesley Delmenico, a US professor of theatre studies, approached the organisation about doing a theatre piece together. “We always felt aggrieved that it had been hidden from history,” Longstaff explains.

With Delmenico writing and directing and Longstaff producing, No Bad Women only did a few pilot shows on a shoestring budget in 2015. But then one of the actors got back in touch and suggested they do another run in light of #MeToo. They were able to pull a production together through crowdfunding, small grants and donations of props and costumes from friends. Though it’s based on a decades-old trial, No Bad Women brings together two growing conversations of the last five years – women’s rights and the decriminalisation of sex work – and tells a story that will remain relevant until something changes.

It arrives just as End Violence Against Women have launched a legal challenge against the CPS after figures showed that rape prosecutions in England and Wales had fallen to their lowest level in over a decade. In a piece for the Guardian, EVAW co-director Rachel Krys wrote that this was due to a “covert and frankly reckless shift in CPS process”, and Longstaff echoes the same. “They’ve encouraged more women to come forward, but then the door is shut in your face because, to some degree, they’ve changed their prosecution policies to make it less likely that they’ll take cases to court.”

The #MeToo movement was decades off when this trial took place, but No Bad Women highlights and counters its most obvious blind spot – the failure to factor class into who gets heard in the first place. The play’s title comes from the slogan “no bad women, just bad laws”, which is often used at protests for sex workers rights. It’s a simple statement with a big message behind it. Namely, calling bullshit on the tendency – especially among policy-makers – to discuss sex work as a moral issue rather than economic one.

This is partly why Adams and Longstaff feel the private prosecution case is so relevant today, and why it’s significant that that sex workers were at the helm all those years ago. This was a fight undertaken by two working class women who were determined to prosecute a man they knew to be dangerous to society, despite all the disparagement and disrespect they faced as sex workers.

“I hope it’ll help change the way that sex workers are characterised, and that people will be able to see much more that sex workers are actually spearheading a movement against violence that is beneficial to all women,” says Adams. “It’s not every day that sex workers take their rapists to court.”

No Bad Women will run from the 1st of November to the 14th of November (except Sundays) at Clean Break in Kentish Town. Tickets can be bought here.

https://www.vice.com/en_uk/article/ne8md8/sex-workers-first-private-prosecution-rape-uk