Tribune: Sex Workers Unite and Take Over

The English Collective of Prostitutes was founded fifty years ago to protect sex workers. Despite the progress they have made in the years since, the industry remains criminalised — and exploitative and unsafe as a result.

(Credit: Crossroads AV Collective.)

On November 17, 1982, fifteen masked women walked, in groups of twos and threes, into the Holy Cross Church in London’s King’s Cross just as the evening service was coming to an end. Clutching sleeping bags, blankets and, in some cases, their young children, they nestled into pews at the back, settling in for what would become a twelve-day occupation of the church.

The women were members and allies of the sex worker-founded-and-led organisation, the English Collective of Prostitutes (ECP) — and they were there, as they told the priest after his service, to protest police brutality, illegality, and racism against sex workers in the local red light area. That night, with the priest’s backing, they locked the church doors; and by the time they opened them again at 8am the next morning, the press were already waiting outside.

Over the next fortnight, the women spent their time giving interviews, welcoming supporters and state representatives and, most importantly, strategising. Their demands were clear: end police harassment; stop arresting sex workers and their partners (and arrest rapists and pimps instead); stop separating mothers who do sex work from their children; and protection, welfare, and housing for women who want to exit the sex industry. By the end of the twelve days, these demands had, ostensibly, been met.

Although the occupation wasn’t the ECP’s first protest action, and despite many of their promised demands eventually unravelling, the event would become a pivotal turning point for sex workers in the UK, helping to birth the modern sex worker rights movement. ‘People began to look at sex workers in a different way after the occupation,’ says Nina Lopez, an early ECP organiser. ‘Once you’re making a struggle, people have to consider the case you’re making. They can’t just go by whatever prejudice they read about.’

In the years since, attitudes to sex work and sex workers have, in many ways, transformed — in no small part buoyed by the work of the ECP, founded fifty years ago this year. In their work over the last half-century, the organisation has created the first ‘know your rights’ guide for sex workers; protested police abuse and the murders of sex workers; fought evictions, raids, and the deportation of migrant sex workers; supported sex workers in court; and campaigned tirelessly for their longstanding demand: the total decriminalisation of sex work.

But, despite ECP’s monumental successes, the stakes are still high for sex workers today, whose work not only remains criminalised, but who face growing threats to their rights and safety. In most of the UK, selling and buying sex isn’t illegal, but associated activities are. For instance, it’s a crime to manage a brothel, ‘cause or incite prostitution’, and to solicit sex in a public place. In practice, this means that sex workers can’t legally work together for safety, nor share advice with one another, and, if they’re working on the street, are forced into more isolated (and therefore dangerous) areas to avoid police detection. At the same time, MPs in England and Scotland are pushing to implement the Nordic Model (already in place in Northern Ireland), which would criminalise buyers of sex — an approach that’s been proven to make sex work more dangerous and heighten violence against sex workers.

So, to celebrate their fiftieth anniversary, this is the history of the ECP, told by those who’ve been fighting from the very beginning and those they’ve helped.

‘For Prostitutes Against Prostitution’

The ECP was founded in 1975 by two migrant sex workers, who were inspired by church occupations and strikes by sex workers in France that same year. It felt like a call to action; it was the first time they’d seen sex workers fight for their rights — and actually be heard. ‘They were bold, they were not self-conscious, they had said what they wanted, and they were together,’ Selma James, the ECP’s first spokesperson, says of the French sex workers. ‘This is how [ECP’s founders] wanted to see themselves: as part of a movement.’

Yet they couldn’t be the face of this movement. ‘They saw the possibility of sex workers having their autonomy and a public presence that was theirs, but they knew that they couldn’t be public themselves,’ says James. In the seventies and eighties, attitudes to sex workers were, in large part, punitive and dehumanising — perhaps best exemplified by the response to the murders of sex workers by the Yorkshire Ripper. ‘Some were prostitutes’, attorney general Michael Havers said of the victims at the time, ‘but the saddest part is that some were… totally respectable women.’

And so, they asked James, a feminist activist, co-founder of the International Wages for Housework Campaign, and, above all, a married non-sex-working woman, to speak for them. The pair drafted a manifesto, of sorts, called ‘For Prostitutes Against Prostitution’. It outlined their stance and objectives: that women should be paid for all labour, including housework and sex, and that prostitution is no different to other forms of waged work. ‘Every alternative to prostitution is either another form of prostitution or terrible poverty or both,’ they wrote. ‘To put forward these alternatives is to support prostitution — not prostitutes.’

‘Once they’d written it down, it was as if the whole thing was clarified,’ reflects James. ‘It said: “If women had money, they wouldn’t be sex workers.” That was so obvious. We wanted to make it clear that women were on the game for one reason only, and that was money. We used to joke: “Does good money make women bad?”’

The Girls’ Union

There was, as James puts it, ‘no excitement in the women’s movement’ about ECP’s launch — but that didn’t stop them from growing. By 1976, the organisation’s HQ, The Women’s Centre — first located in King’s Cross and now in Kentish Town, known as the Crossroads Women’s Centre — was, according to James, ‘a sex worker haunt’. The centre also housed Women Against Rape, as well as Women of Colour in the Global Women’s Strike and Queer Strike, both of which, along with ECP, were autonomous groups within the Wages for Housework Campaign. This is partly how ECP’s network grew, bringing together sex workers, non-sex workers, women of colour, lesbians, migrants, students, and more. ‘It became a place where women were comfortable and protected,’ she adds. ‘They felt it was their place.’

This drew the ire of the police. ‘Once you began to organise as women, that attracted the worst in the police,’ says James. ‘And as soon as you were organising with sex work, there was no pally relationship at all.’

By the early eighties, in the lead up to the church occupation, sex workers’ relationship with the police had soured monumentally. And it wasn’t just sex workers. Uprisings against racist and brutal policing were spreading across the country. At the same time, the anti-porn lobby was pushing for more censorship and control of the sex industry, all while widespread poverty was pushing more women into sex work (those traveling into London from the north of England even became known as ‘Thatcher’s girls’).

Tensions were high. ‘[Sex working] women in the eighties describe an enormous amount of corruption within the police force,’ says Adams. ‘They say that people would get arrested, charged, and fined on a rota.’

James alleges that the police were also protecting pimps. In her retelling of the church occupation, titled Hookers in the House of the Lord, James writes: ‘When threatened with having their kneecaps broken if they didn’t hand over their money regularly, women would go to the police, describe the man, the car, and the licence plate, and the police would tell them, “Come back when your kneecaps are broken”.’

Things worsened after the ECP launched the first ever women-only legal service in Britain, called Legal Action for Women (LAW), offering sex workers legal advice and representation in custody cases, evictions, and illegal arrests. At the time, it was the norm for sex workers to plead guilty, even if they were arrested while, say, shopping or waiting at the bus stop (and not soliciting). Once LAW came along, more sex workers felt emboldened to plead not guilty — and soon, they started to win. ‘As the community changed, the women changed,’ says James. ‘They had guts.’ And thus, ‘the girls’ union’, as ECP and LAW came to be known, was born.

The police, ECP say, were furious. They amped up their harassment, specifically targeting women who used the centre. ‘We did the occupation to expose that and stop it,’ says Lopez. Although the occupation brought light to police harassment of sex workers, it didn’t stop it. As per research shared by ECP, 42 percent of street-based sex workers in London say they have experienced violence from the police, with marginalised sex workers, like trans, migrant women and women of colour being . ‘The only thing that’s changed is the way policing is presented,’ says Adams. ‘Today it’s presented as safeguarding, but it’s just more surveillance, repression, and persecution.’

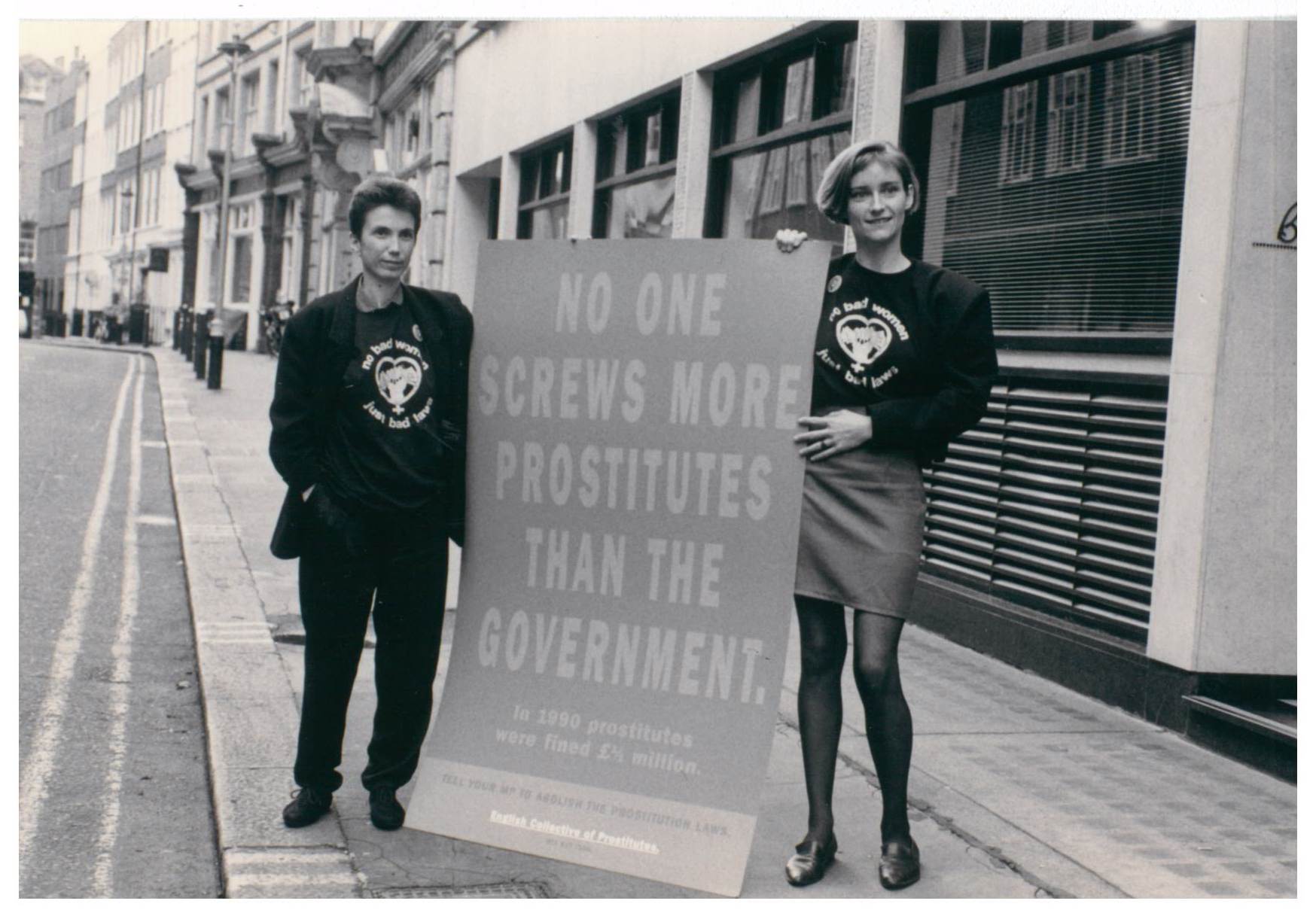

No Bad Women, Just Bad Laws

LAW still runs today, and remains a key reason why sex workers seek out ECP. There’s been many historic successes. In 1995, ECP, working with Women Against Rape, helped two sex workers bring a private prosection against a man who, in separate instances, had raped them at knife point. ‘The police line was, “If you’re a prostitute, you can’t be raped”,’ says Lopez.

‘It was very telling because it showed in precise detail the prejudice,’ adds Adams. ‘The Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) had refused to prosecute, describing the women as “unreliable witnesses” — not based on speaking to them, but purely on the fact that they were sex workers. But we got a conviction on the exact same evidence that the CPS had in front of them.’

And the work has never stopped. In the 2000s and 2010s, ECP spearheaded campaigns against raids on flats in Soho, where sex workers lived and worked, taking legal action to fight against evictions (and winning). There’s also the daily casework that doesn’t make headline news, but is often life-changing for sex workers.

Iris, a mother who’s been working as an escort on and off for eight years, sought help from the ECP when her home was raided and she was accused of controlling prostitution and trafficking. ‘All I did was help other migrant women — many of them single and with little or no English — by screening clients, picking up calls, finding safe housing, and helping them access healthcare and language support,’ she says. ‘For this, I lost my home. Without ECP, I don’t think I would be alive today. Their support and open arms gave me strength to keep going, even though I’ve been under investigation for nearly three years.’

This criminalisation keeps women trapped in sex work. Jean, a mother who’s been selling sex for twenty-five years, was convicted for brothel-keeping after she was found to be working in a flat with one other woman. ‘Whenever I’ve been fined [for prostitution offences], I have to go back onto the street to try to get the money to pay off the fine,’ she says. ‘I wanted a job in caring, but when they did a DBS check, I lost the job, even though I haven’t been in trouble for years.’

‘No One Screws More Prostitutes Than the Government’

Today, one of the biggest threats to sex workers is the supposed worker’s party. In June, Labour MP Tonia Antoniazzi put forward amendments to the Crime and Policing Bill that would criminalise clients and any associates of sex workers, including drivers, friends and family, and sites that sex workers use to advertise. The amendments were, thankfully, dismissed — for now. (In Scotland, Alba Party member Ash Regan has introduced a bill that would criminalise clients, i.e. implement the Nordic Model, which sex workers are currently fighting against.)

‘For a lot of years, we’ve been up against a layer of professionals who’ve smothered sex workers’ voices and experiences and put forward their own agenda,’ says Adams. ‘But now we’re up against Labour women MPs, who are the ones pressing for more criminalisation, more police powers, and more immigration controls.’

There’s also been an uptick in police raids under the guise of anti-trafficking, which Adams says target migrant women. ‘It’s a clever campaign really to frame it as saving victims of trafficking because no one’s going to say, “It’s bad to stop trafficking”, but that’s not what it is,’ she continues. ‘And yet feminist organisations and MPs have gone along with it.’

Government policies, including austerity cuts and the two-child benefit cap, are also making women poorer, especially those of colour and their children. As poverty grows, more women are being forced to turn to sex work to pay the bills, feed their families, or get themselves through school.

‘There is a class struggle going on within the women’s movement, and everybody knows it,’ says James. ‘I’ve heard feminists defend the police against women — they are concerned with a certain kind of morality, which is no use to us.’

While it does feel like a particularly scary moment for sex workers, there have been many transformations over the last fifty years that have improved their lives. The explosion of OnlyFans has helped, to an extent, destigmatise parts of the sex industry, with younger people more open-minded about sex work than previous generations. A recent survey found that most people in the UK now think sex work should be decriminalised.

‘The internet has enabled sex workers to speak on their own behalf,’ says Adams. ‘It’s not across the board by any means — mums, migrant women, and homeless women [can’t so easily be public] — but it has shifted. The struggle continues, but the movement is getting stronger.’ This is perhaps best exemplified by the arrival of new sex worker-led organisations, including SWARM, Decrim Now, National Ugly Mugs, Safety First Wales, and Scotland4Decrim.

‘The community is a very supportive one,’ says Adams. ‘The women who stick around aren’t only interested in getting justice for themselves, they want it for their sisters. ECP has been a lifesaver for me, not only because it’s helped me defend myself against injustices, but because it’s helped me understand my own life and how I fit into society.’

At ninety-five, James has spent forty-five years of her life fighting with the ECP. When we meet, she is as articulate as she was in a video from the 1982 church occupation — and as determined, too. ‘There was a way in which we changed each other,’ reflects James. ‘Not only because some of us were sex workers, but because we have an idea of our worth, how we want to be treated, and what we believe we’re entitled to. And women want money because they’re entitled to it.’ ‘I have no doubt that sex work will be decriminalised,’ she concludes. ‘Women have a right to do what they like with their bodies.’

—————-

About the Author

Brit Dawson is a writer and editor whose work mostly delves into sexual subcultures, sex work, women’s rights, and sex and relationships, exploring how each intersects with technology, politics, and culture.

https://tribunemag.co.uk/2025/10/sex-workers-unite-and-take-over